When I was eight, my cousins moved from Minnesota to Colorado. They talked up the mountains and when I saw pictures of them, I wanted to be there, on top of one, to feel the wind whipping in my face, to look down on the world. I began looking at maps, specifically the Kids Rand McNally Road Atlas I’d coned my mom into buying from the Scholastica book fair, and plotting a trip out west. But I grew up in Minnesota, far from the mountains, and my family never traveled outside of adjacent states or provinces. At eighteen I’d still never been out of the upper Midwest.

It would take me years to learn what mountain climbing entailed. First, there was a failed attempt at South Dakota’s high point. Several years later, despite taking up running in between, I failed again, this time at Colorado’s Long’s Peak.

Then I met and married Erik, who had backpacked in the mountains and successfully climbed Washington’s Mount Rainier. A week after marrying, when I was 23, we moved across the country from Minnesota to Rochester, New York, just a few hours drive from the Adirondacks and Lake Placid, famed for hosting both the 1932 and 1980 Winter Olympics..

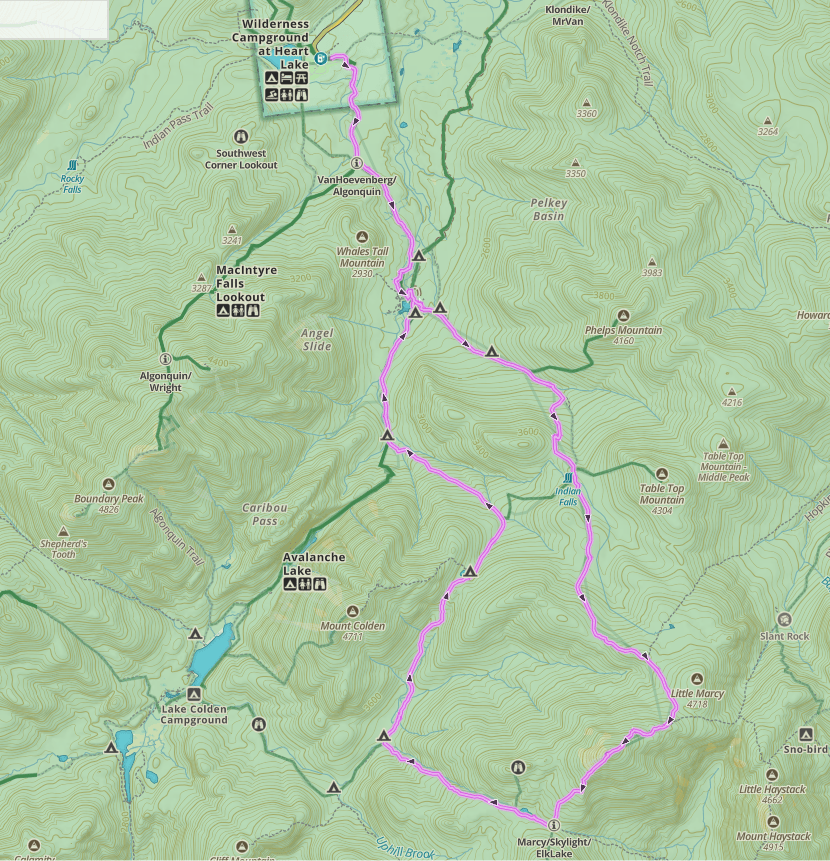

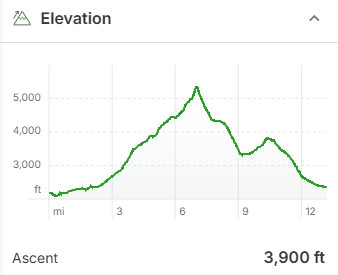

Always up for a summit, Erik agreed to my weekend plan of hiking Mount Marcy, New York’s highest point. On Friday evening, we drove up to the Heart Lake Trailhead, arriving after dark, and set up our tent in the campground. We planned for a day hike on Saturday to bag Marcy, and then do some rollerskiing on Sunday. At 5,344 feet, Marcy rises some 3,000 feet above the valley along with 45 other formidable summits above 4,000 feet. Erik and I had honeymooned the month before, hiking the 100 mile trek around Mount Blanc in the Alps, and were accustomed to nineteen mile days with 6,000 feet of vertical. Hence, we figured the fifteen mile, 3,000 foot vertical loop I’d chosen with a summit of Marcy would make for an easy day.

We began our ascent of Marcy at 8:00 am on a cloudy morning in September with our friend Blake, who was training in nearby Vermont with the National Guard Biathlon Team. Blake had done some serious hiking in the Beartooths of Montana the month previous with our mutual friend Bjorn and was familiar with rough terrain and big vertical days as well. The leaves were in full peak and shades of yellow, orange, and red surrounded us as we gradually gained elevation on the two miles to Marcy Dam, the first notable landmark and where our loop began.

After Marcy Dam, the trail abruptly climbed steeply in a series of gigantic steps of rocks and tree roots. When standing, I looked straight ahead into the mountain slope just five feet in front of my face. Within two giant steps, my feet were at the level my eyes were just looking. These steps were so big, often my legs weren’t tall enough and I looked for rocks or roots to grab to use my arms to help pull me up. I’d never used my upper body strength on any hiking trail before.

“What is this!” I grumbled to my companions.

“Were crawling up a waterfall,” Blake joked with enough sarcasm to know he, too, was shocked by Marcy’s prowess.

Perhaps his comment would’ve been funny, except that at times, water cascaded over the rocks we climbed up.

The clouds hung low but didn’t rain on us. The vegetation was lush off the trail in the forest. Anything not routinely used as a hand or foot hold was covered in thick moss.

The trail kept on like this, colossal step after step, me often reaching for a rock or root to help my ever fatiguing legs reach the next ledge. The tree roots, worn smooth from the hands and feet of the hikers before me, were slippery, especially in the wet conditions. Occasionally the roots were covered in mud, and then so slick I had to find a different hand or foot hold. The soil had long ago eroded away, exposing jagged rocks underneath that bit into my feet even through the soles of my shoes. Sometimes, when I went for a hand hold on a rock, it flaked off. This sure was a different trail from the wide and flat ones in the state parks back in Minnesota. This was even a much different trail from those in the Alps, that maintained a much more shallow grade and beckoned with near constant views. I second-guessed my intentions of mountain climbing more than once. This was supposed to be easy.

After climbing 3,000 vertical feet, we came upon a flat bog just a few hundred feet below the summit.

“What? A bog at 5,000 feet in New York?” Erik declared our surprise as we made our way over a series of wooden bridges to avoid soaking our feet in the spongy ground.

From there to the top were slick granite slabs. We scrambled to the top, sometimes grabbing hand holds when the rock got steep. After four hours and six miles, we arrived at the summit of Mount Marcy. The wind was blowing and we were in the clouds. Soon we were soaking wet. Despite our hard-earned effort, we were shrouded in the fog and disappointed there was no view.

We could have turned around and gone back the way we came, but we were getting cold on the exposed summit and needed to descend to the forest for warmth. So without discussing our options, we continued on our circle route, four miles farther than had we retraced our route up, somehow assuming the other trails couldn’t possibly be as hard. As we scampered off the backside of the mountain, this stretch also a polished granite slab in the mist, my feet slipped out from under me and I landed on my butt.

Once back in the trees, the trail descended precipitously on more large boulders gnarled with roots. With every step, I hesitated, trying to decide whether I should just jump, or find smaller steps, or hold onto a root or rock, or turn around and go down backwards. The trail continued steeply down as the afternoon hours passed, my knees aching more with each step. The guys had to keep waiting for me. My ankle tendons kept tweaking in all directions as I landed on uneven surfaces and jammed my feet between rocks. Finally, after we’d descended 1,000 feet, we came to a trail junction and the next trail flattened out for awhile as we made our way by Lake Tear of the Clouds.

Only the hiking was still cumbersome. Instead of a nice level path, we balanced on rocks and skirted mud puddles to stay dry. Soon the trail dropped again to the next intersection. At least it had stopped raining but my feet burned from the sharp rocks, my lower legs seared from the contortionist moves on the off-camber surfaces, and when I took big steps down, my knees screamed in pain.

We turned onto the Lake Arnold Trail, towards Marcy Dam. At the beginning of the day, I’d had aspirations of bagging another high peak, like Algonquin, but those aspirations had faded on the backside of Marcy. Even on this trail, without crossing contour lines, the going was slow with so many rocks. We hiked through a swamp with multiple deteriorating bridges composed of double wooden logs chopped off on top for a smooth walking surface. Some bridges were broken and we had to balance on only one log. Others were broken in the middle and we walked down one side and then jumped to the other side to walk up. Some bounced up and down from our weight. We crossed one at a time, Blake taking up the rear.

“Oh shit!” Erik and I heard from behind us followed by the sound of water splashing as one of the rotted logs gave way on Blake, leaving him in the swampy water. Fortunately it wasn’t too deep and he was able to get back on some stable logs shortly thereafter. By now the sun was starting to poke through the clouds.

“When we were on the Marcy summit we should’ve just gone back down the way we came,” Erik said solemnly as the trail climbed back up to Lake Arnold. He was, of course, right. How I wished we had. At least I was faster going up than down, but going up also meant we’d have to go back down and the trail condition held little promise of a gentle grade. Indeed, shortly after Arnold Lake, the trail declined again. I struggled to find a rhythm and as the sun got lower in the sky, I took bigger and bigger steps, aggravating my painful knees.

By the time we stumbled into Marcy Dam, the sun was setting. We took some sunset photos and then continued back to the trailhead. From here the trail leveled out and the rocks were much smaller but our legs were so tired we weren’t walking very fast. As the last light in the sky faded away, our progress slowed further as we carefully felt every rock and root with our feet before placing steps. Foolishly, we’d assumed we would be back well before sunset and hadn’t brought headlamps, greatly underestimating the difficulty of the Adirondack trails. There was no moon and it fell completely dark before we made it back to the trailhead and our nearby camp.

When we finally hobbled into camp, eleven hours and sixteen miles later, we were too tired to cook dinner. Instead, we rolled into our tents, humbled by Marcy. The next morning, we woke up and drove home, having had enough Adirondack adventure for the weekend. Marcy was my first state high point. I wasn’t certain I wanted to do another. Sure, the wind was whipping, but there was nothing to see in the clouds.

Despite gaining only 3,000 feet of elevation, Marcy’s steep, rocky, and rooty trails stunned us. It was our first introduction to hiking “out East” where there’s no concept of switchbacks and the trails literally go straight up the mountains with frustratingly few views amidst the trees. Over the next many years, we’d learn only the off-trail summits “out West” rival the New England state high point trails and there are almost always superior views.

And that trail where the log bridge gave way on Blake? It was closed at the end of the season by the forest service due to disrepair.

One thought on “The First One: Day Hiking New York’s Mount Marcy”